Volt says YES to a reform of property taxation

Switzerland is one of the few countries that applies an imputed rental value and taxes it under the income tax. Many property owners consider this rule unfair; accordingly, there have been repeated political initiatives to abolish it. In light of high private indebtedness, distortive incentives, and counterproductive deductions, a system change has been set in motion. We see these issues as core weaknesses of the current system and, despite reservations, support the shift in property taxation.

The system change

The reform consists of two interlinked legislative proposals:

(I) Federal Act on the Reform of Owner-Occupied Housing Taxation (including the abolition of the imputed rental value) → already passed by Parliament; no referendum was called.

(II) Federal Decree on Cantonal Property Taxes on Second Homes → subject to a mandatory referendum (this is what we will vote on).

Important: Proposal (I) only enters into force if proposal (II) is also approved. A rejection of (II) therefore blocks the entire reform.

As part of the reform, the imputed rental value is abolished for both primary and secondary residences. As a fiscal offset, deductions for mortgage interest and maintenance are eliminated, and deductions for energy-efficiency renovations are shifted to the cantonal level. There, the cantons may decide for themselves whether, and to what extent, to continue such deductions. To ensure first-time homeownership does not become unattainable, a first-time buyer deduction will be introduced:

Married couples who are not legally or factually separated: 10,000 CHF, reduced each year by 10% (i.e., 1,000 CHF).

Single persons: 5,000 CHF, reduced each year by 10% (i.e., 500 CHF).

Owners of rental properties may continue to deduct mortgage interest on a “pro-rata restrictive” basis, i.e., in proportion to the share of their rental properties in their total assets (excluding their owner-occupied home). If the rental properties are held as private assets, maintenance costs, the costs of refurbishing newly acquired properties, insurance premiums, and third-party management fees can be deducted in full.

As a compromise, the cantonal property tax on second homes has been tied to the reform. This allows tourism-oriented cantons to offset revenue losses resulting from the abolition of the imputed rental value on second homes. The cantons can decide for themselves whether to introduce this tax and at what rate. It may only be levied on second homes that are predominantly owner-used (i.e., not rented out).

Volt's Position

The current system is dysfunctional, harms Switzerland, and favors the very wealthy

Switzerland has the highest private debt ratio in the world. For comparison: in Switzerland it stands at 126%, while in Germany, where interest deductions are only allowed for rented properties, it is 53.5%. This single comparison is only partly meaningful, but it symbolizes the perverse incentives in the Swiss system. The debt ratio is twice as high as in the euro area. High indebtedness weakens the economy and poses a systemic risk for Switzerland.

What’s more, mortgage interest deductions drive up prices without increasing the homeownership rate, since the primary beneficiaries are the very wealthy.

The same applies to deductions for energy-efficiency renovations: many of these investments would be made even without tax incentives. In practice, they often amount to a tax break for the well-off.

The conclusion is clear: we need a system change.

The reform is an improvement over the status quo

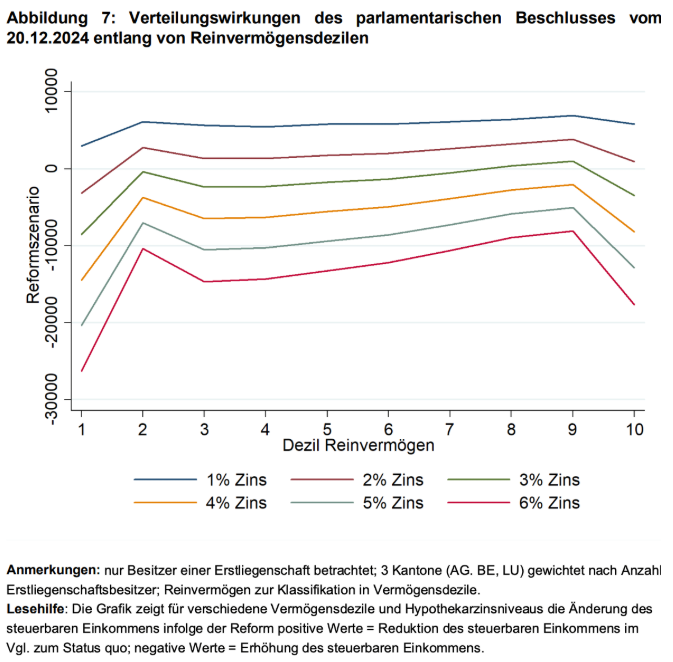

Limiting mortgage interest deductions to first-time buyers in the future significantly curbs the misaligned incentives described above. With a view to potentially higher interest rates (above 1.5%), the support could have been set a bit higher and split evenly between principal amortization and mortgage interest. Such a design would have strengthened the support effect: falling mortgage balances reduce future interest burdens and make further amortization easier. In its current form, at least, the reform still provides targeted support without primarily benefiting the very wealthy.

The elimination of deductions for value-preserving renovations is regrettable: depending on the loan-to-value ratio, owners of properties in need of refurbishment will be among the relative losers of the reform during the first 10 to 30 years. Even if this group is small at today’s interest levels, this rule counts among the less successful adjustments.

We view the potential elimination of deductions for energy-efficiency renovations as less problematic. Due to high windfall effects, the intended steering effect has so far been missed. Instead, climate laws and other instruments should be used to introduce targeted measures that are more effective and, in particular, support those owners who could not otherwise afford such renovations.

Introducing a cantonal property tax on second homes is welcome in light of the reform’s fiscal risks; it brings no apparent downsides.

The reform is not perfect, but it represents a clear improvement over the status quo.

The beneficiaries are more diverse than just “the rich”

Retirees with little or no mortgage debt generally benefit the most: for them, the imputed rental value disappears without losing any significant deductions. This holds across income groups and, in relative terms, leads to noticeable tax relief for many.

Quelle Bilder: (I) Eidgenössische Steuerverwaltung: https://www.estv2.admin.ch/stp/notizen/stp-notizen-2025-verteilwirkungen-emw-de.pdf

(II) Bundesamt für Statistik, “Wie wohnt die Mitte”

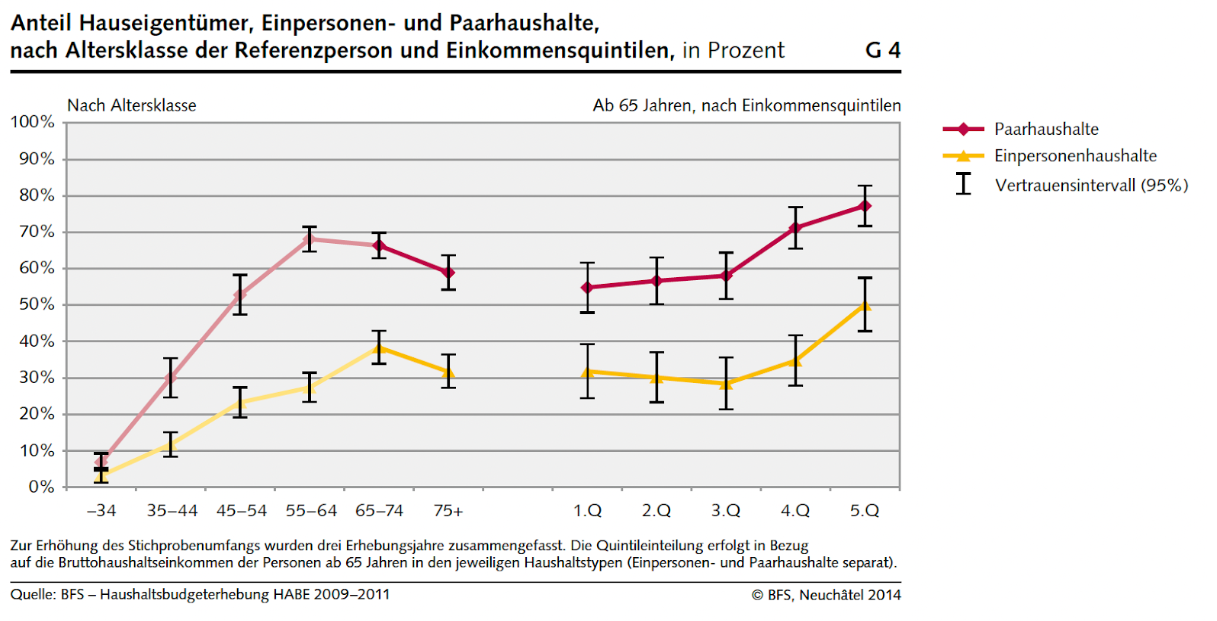

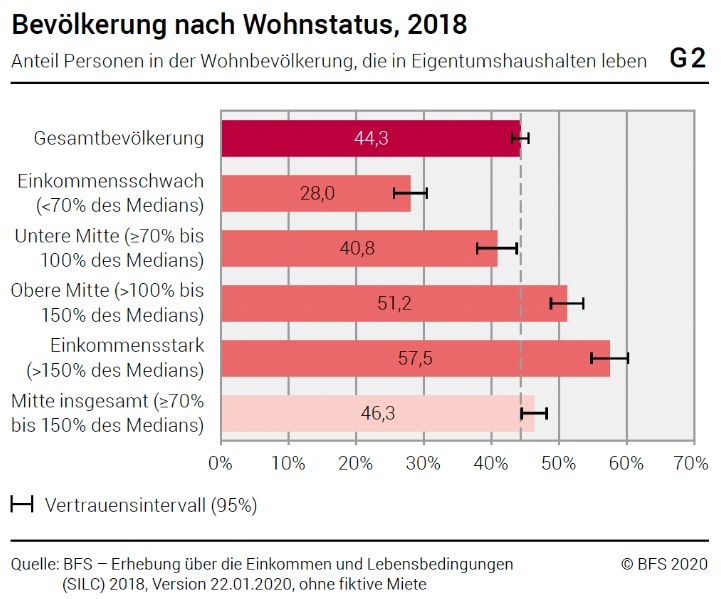

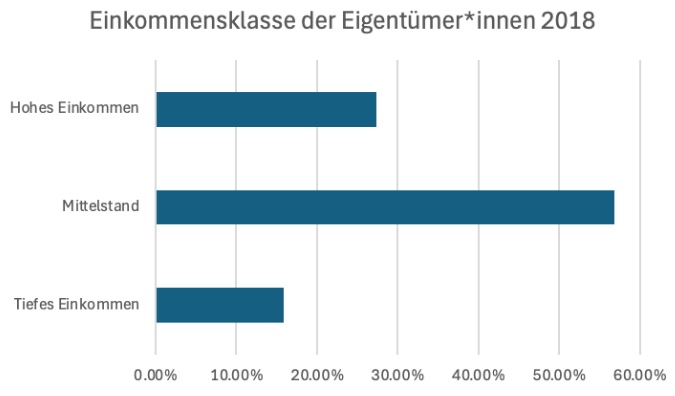

First-time buyers benefit in a targeted and time-limited way through the new interest deduction in the first ten years after purchase. Highly indebted households, by contrast, only gain when interest rates are low; if rates rise sharply, the end of the interest deduction can tip the balance into the negative. While many homeowners are found in the top 25% of incomes, the converse is not true: roughly every second person in the middle-income group lives in owner-occupied housing, and this group makes up more than half of the population. Of course, within this group it is primarily the wealthier segment that has high ownership rates. The richest are, relative to their income class, the most affected within their class, but they are also only a small share of the overall population. For the distributional question (“Who pays for what?”), what matters is how large a share of the homeownership “pie” each income class holds, and middle incomes are well represented here (see the distribution of income and homeownership).

The very wealthy are also not automatically winners from the reform, as they are often highly leveraged, something the tax administration also notes. Renters do not benefit; in the short term, they will even count among the losers. On the one hand, the proposal does not affect them directly; on the other, there are fiscal risks: if a deficit occurs, plausible in the short run, though likely smaller than the tax administration assumes, the burden will depend on the chosen financing strategy, which may also affect renters.

Quelle Bilder: (I) Eidgenössische Steuerverwaltung: https://www.estv2.admin.ch/stp/notizen/stp-notizen-2025-verteilwirkungen-emw-de.pdf

Quelle Bilder: (I) Eidgenössische Steuerverwaltung: https://www.estv2.admin.ch/stp/notizen/stp-notizen-2025-verteilwirkungen-emw-de.pdf

(II) Watson.ch : https://www.watson.ch/schweiz/daten/981378073-der-mittelstand-in-der-schweiz-noetiges-einkommen-und-entwicklung

Conclusion

The reform improves a dysfunctional system. It is not perfect, but overall it represents a clear improvement over the status quo. In the short term, compensatory financing will be necessary. Volt will advocate for the most socially fair solution possible so that non-beneficiaries, especially low-income households, are not burdened further.

The removal of deductions for energy-efficiency renovations should be purposefully replaced with effective subsidies. The reform is not an endpoint, but a first step toward a tax system that is not only effective, but also makes homeownership what it should be: a reliable form of retirement security. Along the way, numerous problems remain to be solved, many of them underlying Switzerland’s low homeownership rate, which needs to increase significantly.

Sources

Bundesgesetz über den Systemwechsel beider Wohneigentumsbesteuerung, admin.ch (Link)

Bundesbeschluss über die kantonalen Liegenschaftssteuern auf Zweitliegenschaften, admin.ch (Link)

Wie die hohe Privatverschuldung in der Schweiz einzuordnen ist, Avenir Suisse (Link)

Liste der Länder nach Haushaltsverschuldung, Wikipedia (Link)

The real effects of household debt in the short and long run, BIS (Link)

Wie die hohe Privatverschuldung in der Schweiz einzuordnen ist, Avenir Suisse (Link)

Hypothekar- und Immobilienmarkt: Aktuelle Entwicklungen bergen Risiken für die Finanzstabilität, Universität Luzern, Seite 9-10.

Do People Respond to the Mortgage Interest Deduction? Quasi-experimental Evidence from Denmark, American Economic Journal:Economic Policy; 2021 (Link)

Housing Tenure Choice in Australia and the United States: Impacts of Alternative Subsidy Policies, Real Estate Economics; 2006 (Link)

Mortgage Interest Deductions and Homeownership: An International Survey, Journal of Real Estate Literature rating (Link)

Wirkung steuerlicher Anreize für energetische Gebäudesanierungen und mögliche Hemmnisse bei deren Finanzierung, UVEK S.36 (Link)

immobilien-schweiz-1Q25-d, Raiffeisen S. 23 (Link)

Siehe “Wer Profitiert” in unserem Factsheet

Einkommensmitte, BSF (Link)

Verteilungswirkungen einer Reform der Eigenmietwertbesteuerung, ESTV S. 6 (Link)

Siehe “Wer Profitiert” in unserem Factsheet + “Unklare finanzielle Auswirkungen”